Bread waste + fungi = yarn

The production of new materials from fungi is an emerging research area. In a research project at the Swedish School of Textiles at the University of Borås, wet spinning of fungal cell wall material has shown promising results. In the project, fungi were grown on bread waste to produce textile fibers with potential in the medical technology field.

Sofie Svensson's project addresses, among other things, the UN's Global Goals 9, sustainable industry, innovation, and infrastructure, and Goal 12, sustainable consumption and production, as the project aimed to use sustainable methods in a resource- and cost-effective way, with less impact on people and the environment.

Sofie Svensson, who recently defended her dissertation in the field of Resource Recovery, explained:

“My research project is about developing fibres spun from filamentous fungi for textile applications. The fungi were grown on bread waste from grocery stores. Waste that would otherwise have a significant environmental impact if discarded.”

The novelty of the project lies in the method used – wet spinning of cell wall material.

“Wet spinning is a method used to spin fibres (filaments) from materials such as cellulose. In this project, cell wall material from filamentous fungi was used to produce fibres through wet spinning. The cell wall material from the fungi contains various polymers, mainly polysaccharides such as chitin, chitosan, and glucan. The challenge was to spin the material. It took some time initially before we found the right conditions”, explained Sofie Svensson.

Antibacterial properties

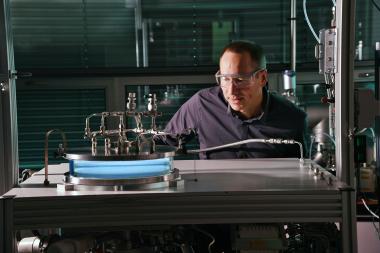

Filamentous fungi were cultivated in bioreactors to produce fungal biomass. Cell wall material was then isolated from the fungal biomass and used to spin a filament, which was tested for its suitability in medical applications.

“Tests of the fibers showed compatibility with skin cells and also indicated an antibacterial effect”, said Sofie Svensson, adding:

“In the method we worked with, we focused on using milder processes and chemicals. The use of hazardous and toxic chemicals is currently a challenge in the textile industry, and developing sustainable materials is important to reduce environmental impact.”

What is the significance of the results?

“New materials from fungi are an emerging research area. Hopefully, this research can contribute to the development of new sustainable materials from fungi”, explained Sofie Svensson.

Interest from the surrounding community has been significant during the project, and many have had a positive attitude toward the development of this type of material.

When will we see products made from these fibers?

“This particular method is at the lab scale and still in the research stage”, she explained.

The doctoral project was conducted within the larger research project Sustainable Fungal Textiles: A novel approach for reuse of food waste.

What is the next step in research on fungal fibers?

“Future studies could focus on optimizing the wet spinning process to achieve continuous production of fungal fibers. Additionally, testing the cultivation of fungi on other types of food waste.”

How have you experienced your time as a doctoral student in Resource Recovery?

“It has been an intense period as a doctoral student, and I have been really challenged and developed a lot.”

What is your next step?

“I will be taking parental leave for a while before taking the next step, which is yet to be decided.”

Sofie Svensson defended her dissertation on 14 June at the Swedish Centre for Resource Recovery, University of Borås.

Read the dissertation: Development of Filaments Using Cell Wall Material of Filamentous Fungi Grown on Bread Waste for Application in Medical Textiles

Opponent: Han Hösten, Professor, Utrecht University

Main Supervisor: Akram Zamani, Associate Professor, University of Borås

Co-Supervisors: Minna Hakkarainen, Professor, KTH; Lena Berglin, Associate Professor, University of Borå

University of Borås, Solveig Klug