Designers make dissolvable textiles from gelatin

Introducing the fashion of the future: a T-shirt you can wear a few times, then, when you get bored with it, dissolve and recycle to make a new shirt.

Researchers at the ATLAS Institute at the CU Boulder are now one step closer to that goal. In a new study, the team of engineers and designers developed a DIY machine that spins textile fibers made of materials like sustainably sourced gelatin. The group’s “biofibers” feel a bit like flax fiber and dissolve in hot water in minutes to an hour.

The team, led by Eldy Lázaro Vásquez, a doctoral student in the ATLAS Institute, presented its findings in May at the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in Honolulu.

“When you don’t want these textiles anymore, you can dissolve them and recycle the gelatin to make more fibers,” said Michael Rivera, a co-author of the new research and assistant professor in the ATLAS Institute and Department of Computer Science.

The study tackles a growing problem around the world: In 2018 alone, people in the United States added more than 11 million tons of textiles to landfills, according to the Environmental Protection Agency—nearly 8% of all municipal solid waste produced that year.

The researchers envision a different path for fashion.

Their machine is small enough to fit on a desk and cost just $560 to build. Lázaro Vásquez hopes the device will help designers around the world experiment with making their own biofibers.

“You could customize fibers with the strength and elasticity you want, the color you want,” she said. “With this kind of prototyping machine, anyone can make fibers. You don’t need the big machines that are only in university chemistry departments.”

Spinning threads

The study arrives as fashionistas, roboticists and more are embracing a trend known as “smart textiles.” Levi’s Trucker Jacket with Jacquard by Google, for example, looks like a denim coat but includes sensors that can connect to your smartphone.

But such clothing of the future comes with a downside, Rivera said:

“That jacket isn't really recyclable. It's difficult to separate the denim from the copper yarns and the electronics.”

To imagine a new way of making clothes, the team started with gelatin. This springy protein is common in the bones of many animals, including pigs and cows. Every year, meat producers throw away large volumes of gelatin that doesn’t meet requirements for cosmetics or food products like Jell-O. (Lázaro Vásquez bought her own gelatin, which comes as a powder, from a local butcher shop.)

She and her colleagues decided to turn that waste into wearable treasure.

The group’s machine uses a plastic syringe to heat up and squeeze out droplets of a liquid gelatin mixture. Two sets of rollers in the machine then tug on the gelatin, stretching it out into long, skinny fibers—not unlike a spider spinning a web from silk. In the process, the fibers also pass through liquid baths where the researchers can introduce bio-based dyes or other additives to the material. Adding a little bit of genipin, an extract from fruit, for example, makes the fibers stronger.

Other co-authors of the research included Mirela Alistar and Laura Devendorf, both assistant professors in ATLAS.

Dissolving duds

Lázaro Vásquez said designers may be able to do anything they can imagine with these sorts of textiles.

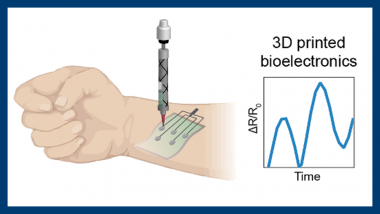

As a proof of concept, the researchers made small textile sensors out of gelatin fibers and cotton and conductive yarns, similar to the makeup of a Jacquard jacket. The team then submerged these patches in warm water. The gelatin dissolved, releasing the yarns for easy recycling and reuse.

Designers could tweak the chemistry of the fibers to make them a little more resilient, Lázaro Vásquez said—you wouldn’t want your jacket to disappear in the rain. They could also play around with spinning similar fibers from other natural ingredients. Those materials include chitin, a component of crab shells, or agar-agar, which comes from algae.

“We’re trying to think about the whole lifecycle of our textiles,” Lázaro Vásquez said. “That begins with where the material is coming from. Can we get it from something that normally goes to waste?”