The Future of Circular Textiles: New Cotton Project completed

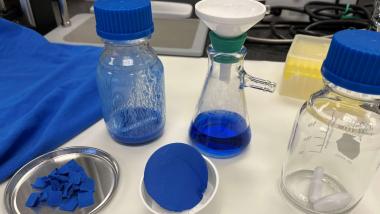

In a world first for the fashion industry, in October 2020 twelve pioneering players came together to break new ground by demonstrating a circular model for commercial garment production. Over more than three years, textile waste was collected and sorted, and regenerated into a new, man-made cellulosic fiber that looks and feels like cotton – a “new cotton” – using Infinited Fiber Company’s textile fiber regeneration technology.

The pioneering New Cotton Project launched in October 2020 with the aim of demonstrating a circular value chain for commercial garment production. Through-out the project the consortium worked to collect and sort end-of-life textiles, which using pioneering Infinited Fiber technology could be regenerated into a new man-made cellulosic fibre called Infinna™ which looks and feels just like virgin cotton. The fibres were then spun into yarns and manufactured into different types of fabric which were designed, produced, and sold by adidas and H&M, making the adidas by Stella McCartney tracksuit and a H&M printed jacket and jeans the first to be produced through a collaborative circular consortium of this scale, demonstrating a more innovative and circular way of working for the fashion industry.

As the project completes in March 2024, the consortium highlights eight key factors they have identified as fundamental to the successful scaling of fibre-to-fibre recycling.

The wide scale adoption of circular value chains is critical to success

Textile circularity requires new forms of collaboration and open knowledge exchange among different actors in circular ecosystems. These ecosystems must involve actors beyond traditional supply chains and previously disconnected industries and sectors, such as the textile and fashion, waste collection and sorting and recycling industries, as well as digital technology, research organisations and policymakers. For the ecosystem to function effectively, different actors need to be involved in aligning priorities, goals and working methods, and to learn about the others’ needs, requirements and techno-economic possibilities. From a broader perspective, there is also a need for a more fundamental shift in mindsets and business models concerning a systemic transition toward circularity, such as moving away from the linear fast fashion business models. As well as sharing knowledge openly within such ecosystems, it also is important to openly disseminate lessons learnt and insights in order to help and inspire other actors in the industry to transition to the Circular Economy.

Circularity starts with the design process

When creating new styles, it is important to keep an end-of-life scenario in mind right from the beginning. As this will dictate what embellishments, prints, accessories can be used. If designers make it as easy as possible for the recycling process, it has the bigger chance to actually be feedstock again. In addition to this, it is important to develop business models that enable products to be used as long as possible, including repair, rental, resale, and sharing services.

Building and scaling sorting and recycling infrastructure is critical

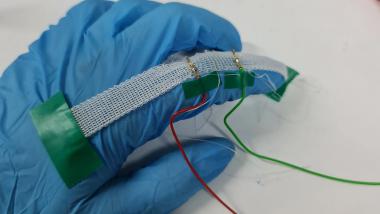

In order to scale up circular garment production, there is a need for technological innovation and infrastructure development in end-of-use textiles collection, sorting, and the mechanical pre-processing of feedstock. Currently, much of the textiles sorting is done manually, and the available optical sorting and identification technologies are not able to identify garment layers, complex fibre blends, or which causes deviations in feedstock quality for fibre-to-fibre recycling. Feedstock preprocessing is a critical step in textile-to-textile recycling, but it is not well understood outside of the actors who actually implement it. This requires collaboration across the value chain, and it takes in-depth knowledge and skill to do it well. This is an area that needs more attention and stronger economic incentives as textile-to-textile recycling scales up.

Improving quality and availability of data is essential

There is still a significant lack of available data to support the shift towards a circular textiles industry. This is slowing down development of system level solutions and economic incentives for textile circulation. For example, quantities of textiles put on the market are often used as a proxy for quantities of post-consumer textiles, but available data is at least two years old and often incomplete. There can also be different textile waste figures at a national level that do not align, due to different methodologies or data years. This is seen in the Dutch 2018 Mass Balance study reports and 2020 Circular Textile Policy Monitoring Report, where there is a 20% difference between put on market figures and measured quantities of post-consumer textiles collected separately and present in mixed residual waste. With the exception of a few good studies such as Sorting for Circularity Europe and ReFashion’s latest characterization study, there is almost no reliable information about fibre composition in the post-consumer textile stream either. Textile-to-textile recyclers would benefit from better availability of more reliable data. Policy monitoring for Extended Producer Responsibility schemes should focus on standardising reporting requirements across Europe from post-consumer textile collection through their ultimate end point and incentivize digitization so that reporting can be automated, and high-quality textile data becomes available in near-real time.

The need for continuous research and development across the entire value chain

Overall, the New Cotton Project’s findings suggest that fabrics incorporating Infinna™ fibre offer a more sustainable alternative to traditional cotton and viscose fabrics, while maintaining similar performance and aesthetic qualities. This could have significant implications for the textile industry in terms of sustainability and lower impact production practices. However, the project also demonstrated that the scaling of fibre-to-fibre recycling will continue to require ongoing research and development across the entire value chain. For example, the need for research and development around sorting systems is crucial. Within the chemical recycling process, it is also important to ensure the high recovery rate and circulation of chemicals used to limit the environmental impact of the process. The manufacturing processes also highlighted the benefit for ongoing innovation in the processing method, requiring technologies and brands to work closely with manufacturers to support further development in the field.

Thinking beyond lower impact fibres

The New Cotton Project value chain third party verified LCA reveals that the cellulose carbamate fibre, and in particular when produced with a renewable electricity source, shows potential to lower environmental impacts compared to conventional cotton and viscose. Although, it's important to note that this comparison was made using average global datasets from Ecoinvent for cotton and viscose fibres, and there are variations in the environmental performance of primary fibres available on the market. However, the analysis also highlights the importance of the rest of the supply chain to reduce environmental impact. The findings show that even if we reduce the environmental impacts by using recycled fibres, there is still work to do in other life cycle stages. For example; garment quality and using the garment during their full life span are crucial for mitigating the environmental impacts per garment use.

Citizen engagement

The EU has identified culture as one of the key barriers to the adoption of the circular economy within Europe. An adidas quantitative consumer survey conducted across three key markets during the project revealed that there is still confusion around circularity in textiles, which has highlighted the importance of effective citizen communication and engagement activities.

Cohesive legislation

Legislation is a powerful tool for driving the adoption of more sustainable and circular practices in the textiles industry. With several pieces of incoming legislation within the EU alone, the need for a cohesive and harmonised approach is essential to the successful implementation of policy within the textiles industry. Considering the link between different pieces of legislation such as Extended Producer Responsibility and the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation, along with their corresponding timeline for implementation will support stakeholders from across the value chain to prepare effectively for adoption of these new regulations.

The high, and continuously growing demand for recycled materials implies that all possible end-of-use textiles must be collected and sorted. Both mechanical and chemical recycling solutions are needed to meet the demand. We should also implement effectively both paths; closed-loop (fibre-to-fibre) and open -loop recycling (fibre to other sectors). There is a critical need to reconsider the export of low-quality reusable textiles outside the EU. It would be more advantageous to reuse them in Europe, or if they are at the end of their lifetime recycle these textiles within the European internal market rather than exporting them to countries where demand is often unverified and waste management inadequate.

Overall, the learnings spotlight the need for a holistic approach and a fundamental mindset shift in ways of working for the textiles industry. Deeper collaboration and knowledge exchange is central to developing effective circular value chains, helping to support the scaling of innovative recycling technologies and increase availability of recycled fibres on the market. The further development and scaling of collecting and sorting, along with the need to address substantial gaps in the availability of quality textile flow data should be urgently prioritised. The New Cotton Project has also demonstrated the potential of recycled fibres such as Infinna™ to offer a more sustainable option to some other traditional fibres, but at the same time highlights the importance of addressing the whole value chain holistically to make greater gains in lowering environmental impact. Ongoing research and development across the entire value chain is also essential to ensure we can deliver recycled fabrics at scale in the future.

The New Cotton Project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101000559.

Fashion for Good